¶ Syntactic Dependency Annotation

Dependency annotation generally follows Universal Dependencies, currently version 2.0, based on McDonald et al. (2013) (see https://universaldependencies.org/en/dep/).

Instructions for some special cases follow below the list of labels.

¶ List of dependency function labels used in GUM

- acl

- acl:relcl

- advcl

- advcl:relcl

- advmod

- amod

- appos

- aux

- aux:pass

- case

- cc

- cc:preconj

- ccomp

- compound

- compound:prt

- conj

- cop

- csubj

- csubj:pass

- dep

- det

- det:predet

- discourse

- dislocated

- expl

- fixed

- flat

- goeswith

- iobj

- list

- mark

- nmod

- nmod:poss

- nmod:unmarked

- nsubj

- nsubj:pass

- nummod

- obj

- obl

- obl:agent

- obl:unmarked

- orphan

- parataxis

- punct

- reparandum

- root

- vocative

- xcomp

¶ Handling copula verbs

The copula 'be' appears primarily in three constructions:

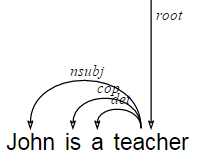

¶ A is B

In the normal predicative construction, the nominal predicate 'B' is the root, and 'A' is the nsubj. The verb 'be' itself is a dependent of the predicate B and takes the label cop.

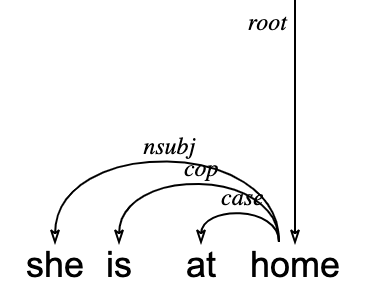

¶ A is in B

Similarly, when the predicate is a prepositional phrase, the convention is to analyze the nominal head of the prepositional phrase as the root. The rest are dependent on the head: the preposition as case, the copula as cop and the subject as nsubj.

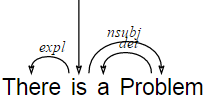

¶ There is A

In the existential construction 'there is A', the verb 'be' is taken to mean 'exist', and is labeled as the root. The subject is A (nsubj) and expletive 'there' is labeled expl.

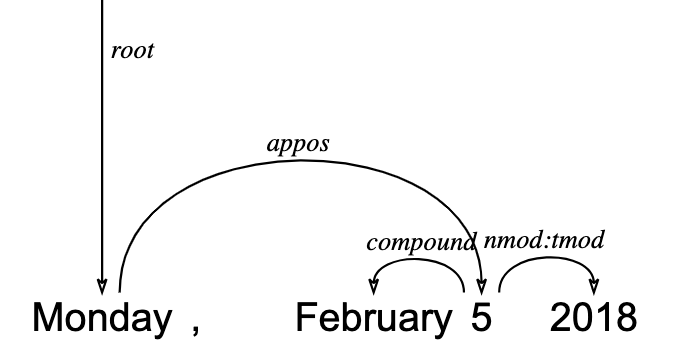

¶ Dates

Dates with multiple coreferent parts are handled as appositions (appos). For example, "Monday, the 5th", constitutes two mentions of the same day. By 'rule of first dibs', the apposition goes from 'Monday' to '5th'. When constructing a calendar date, regardless of the order among 'year', 'month' and 'day', the 'day' is always the head. The 'month' and 'year' are dependent on the 'day', both receiving the label 'nmod:unmarked'. In other words, 'February 5' is a type of '5' (not a type of 'February'); years added to dates are seen as temporal modifiers of the day expression.

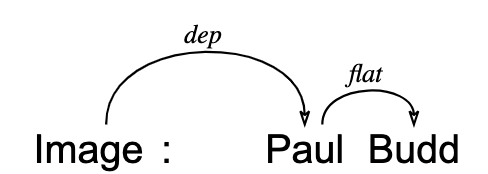

¶ Image credits and quotation attribution

Image credits of the type: 'Image: XYZ' are seen as an individual construction and not analyzed as parataxis or nominal predication (root+nsubj). Instead, the convention is to use the dep label to point from the first part ('image') to the head of the second part. This avoids counting these constructions when searching e.g. for subjects or nominal sentences.

The same logic applies to quotation attribution with a speech verb. For example, in:

"To be or not to be" -- Hamlet

The root is in the quotation, and 'Hamlet' is attached to that as dep. This is not the guideline if a speech verb is present, i.e. 'said' is the root in:

"To be or not to be", said Hamlet.

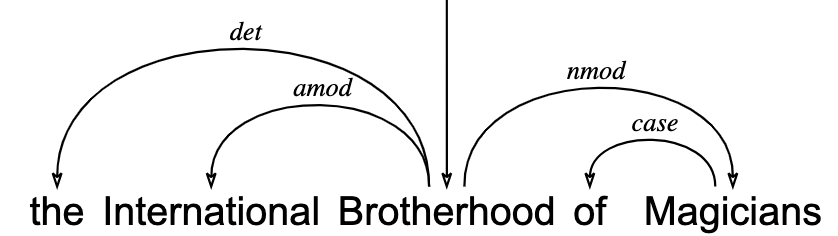

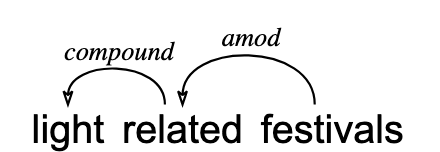

¶ Internal analysis of complex names

Although the proper noun tag is applied even to (capitalized) adjectives in complex names, syntactic analysis should still treat them as adjectives etc. The rationale is that the POS tag can help find names, while a function label such as amod allows us to identify the internal structure of the name in question.

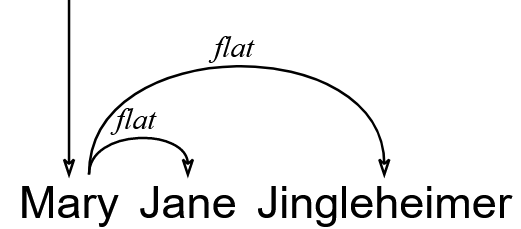

For complex personal names, we make the first token the head, and if we don't know anything about the internal structure, then everything else is flat from that:

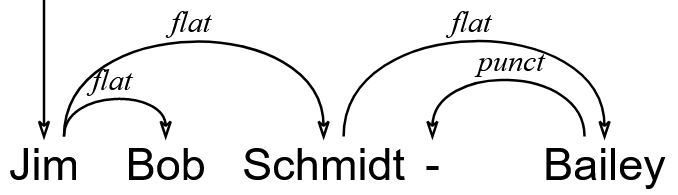

However if there are sub-groups within a first name and a middle or last name, each can form its own 'flat' group, so "Jim Bob Schmidt - Bailey" would be:

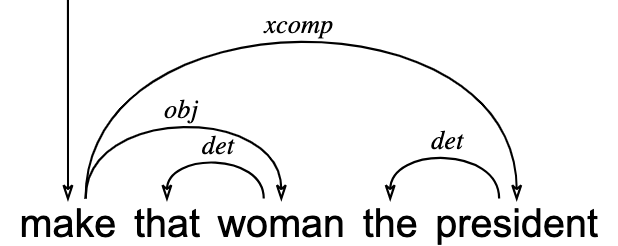

¶ Make A B

The apparent 'double object' construction with 'make' and similar verbs is given a small clause type of analysis, wherein the object of the verb 'make' is seen as the essential role (rather than as the subject of an embedded predication). In other words, 'make A a B' is analyzed as making A to be a B. As a result, the analysis uses the xcomp label emanating from 'make' to signify that the accusative object of 'make' is the same as the subject of the clausal predicate, but the 'thing being made' is internally labeled as the object of the main predication. This can be seen in the image below:

Another way of thinking of this is that the analysis means: make (that woman) (to be the president)

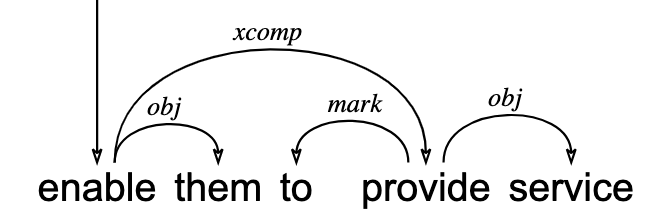

¶ Let N V

Verbs such as 'let' in "let someone do something" or 'allow' in "allow A to do B" are analyzed as governing an xcomp clause, where the noun following the verb acts the object of the main clause, not as the subject of the subordinate small clause.

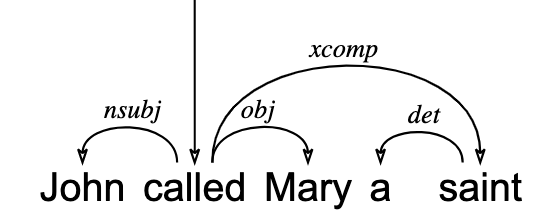

¶ Call, name, etc.

Verbs like 'call' or 'name' appear to take a double accusative object, e.g. "John called [Mary] [a saint]". This makes it hard to distinguish the name argument from the named theme argument. The guidelines instead favor a different analysis using xcomp. The idea is that the naming action creates a direct object (the named) and a small clause with the name as predicate: John performs a naming act, whose object is Mary and the small clause predicate is a saint.

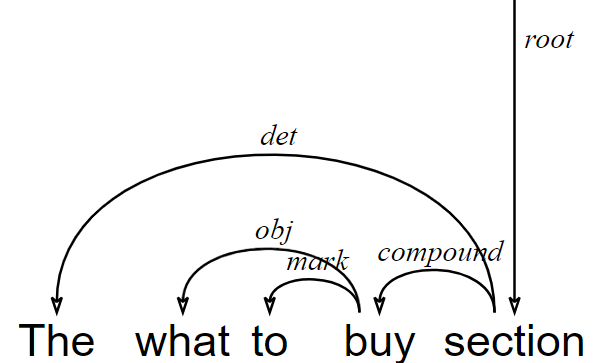

¶ Complex phrases as 'words' (compound modifiers etc.)

In some cases, a whole phrase can be used in place of a single word, e.g. as a compound modifier. In these cases, the complex modifier should be analyzed internally, and its local root is still attached to token it modifies with the normal label.

In the example, 'what to buy' is an infinitive + object with an internal analysis, but it functions much like a compound modifier (cf. 'the shopping section'). For this reason, it is attached at its head (the verb) with the function compound.

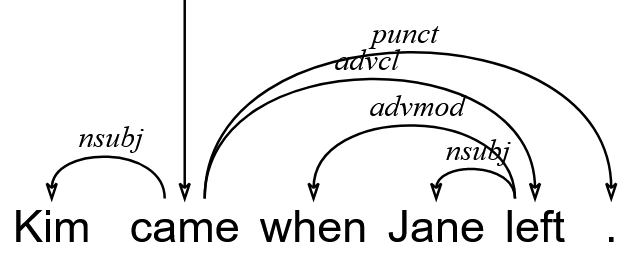

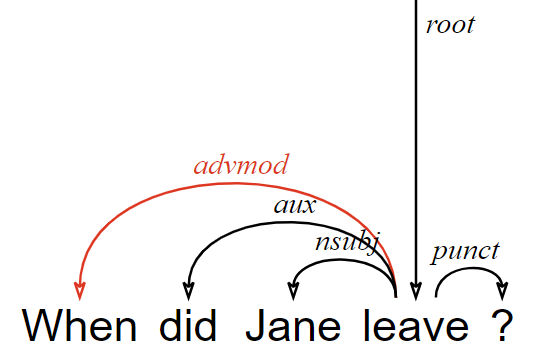

¶ mark vs. advmod

In adverbial clauses, the subordinating conjunction is labeled as 'mark' by convention for 'if' and 'whether' clauses. However for WH adverbs such as 'when' or 'where' we use advmod, which indicates that they are seen as serving the function of an adverbial in the subordinate clause (i.e. representing the 'place where' or 'time when'). In interrogative clauses too, they are labeled advmod. This applies to 'when', 'where' and 'how', paralleling such adverbs as 'then', 'there', and 'thus'.

Compare:

¶ xcomp vs. advcl

Adverbial infinitive clauses, such as purpose clauses, which are not an argument of their embedding clause predicate, are advcl, not xcomp (since they are not complements). A common test to distinguish these is whether or not we can insert 'in order to':

- They expect to come (come = xcomp, cf. ?? they expect in order to come)

- They work to earn money (earn = advcl, cf. they work in order to earn money)

See also the guideline for 'in order to' below.

¶ Analytic comparative and 'than'

Comparative adjectives that take 'than Y' dominate the word/phrase 'Y' as obl and 'than' is case dependent on 'Y'. For analytic comparatives, the word 'more' is seen as advmod to the lexical adjective, and 'than' is governed by the lexical adjective as well (e.g. in 'more expensive than...', expensive governs the other two words).

However, 'more than' in 'more than 5 bags' is treated as fixed from 'more' to 'than'.

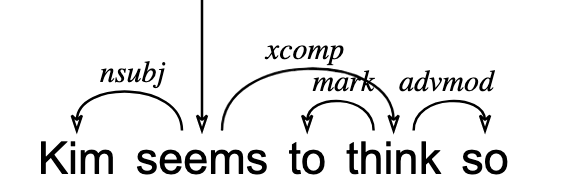

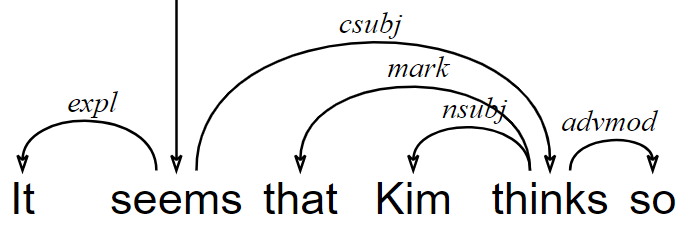

¶ Raising verbs (seem, happen...)

Raising verbs appear to take a subject that actually belongs to a subordinate predicate semantically. The can be identifies by alternations such as "John seems sick" vs "it seems John is sick" or "I happen to own a boat" vs. "It so happens I own a boat". In both cases, the subject is predicated on in the embedded predicate (e.g. happens(I own a boat), not happen(I), or "I happen"). In these cases, a subject 'it' will be attached as expl, and the clause is attached as csubj. Lexical subjects of verbs like "seem" are attached normally to "seem" at the syntactic level, not to the subordinate clause:

¶ Sentence initial 'and'

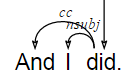

Sentence initial coordinating conjunctions are attached to the root, pointing backwards, with the cc function.

¶ Coordination with adverbial 'so'

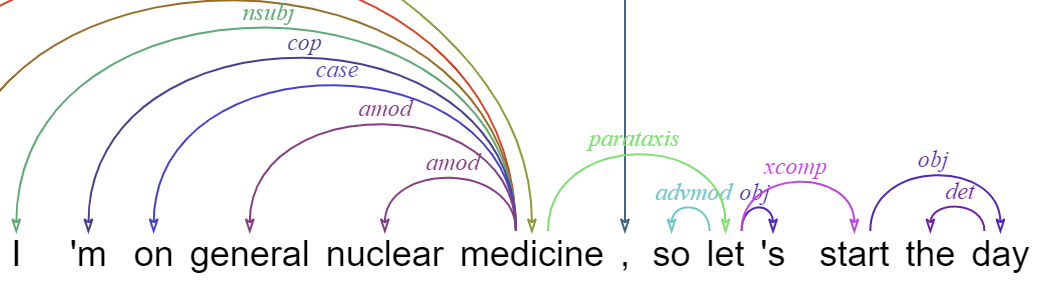

For the adverb 'so' (not to be confused with purpose 'so' tagged IN, or discourse 'so' tagged UH) between two clauses, we attach 'so' as advmod to the second clause (not cc), and connect the clauses as parataxis (not conj):

¶ Attaching footnote markers

Footnote markers (the footnote number) should be attached as dep to the root of the constituent that the footnote refers to. If the footnote refers to the entire sentence, then it attaches to the root. If the footnote refers to a smaller constituent, then its root is the source of the dep arrow.

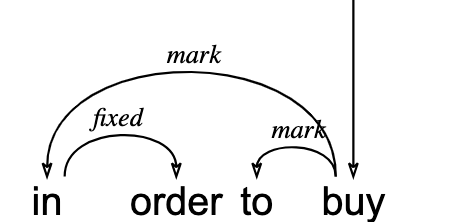

¶ In order to

'In order' is seen as a multi-word expression, which may or may not appear with 'to' (cf. 'in order that'). The function of 'in order' is mark and it is attached at the 'in'. The token 'order' is pointed at with fixed as shown below:

The verb of 'in order to' clause is attached as advcl to the main clause.

¶ Clausal subjects (csubj)

Subject clauses can be full finite clauses, as in "[that they came] annoyed me". But the csubj label can also apply to gerund clauses, as in "[doing that] can cause trouble". In both of these cases, the subordinate clause verb is labeled as csubj to the main clause predicate.

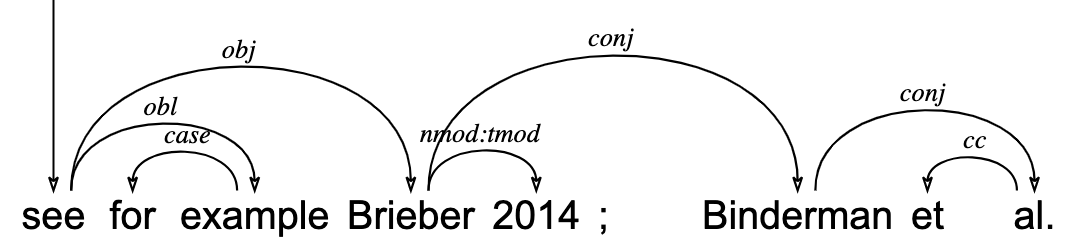

¶ Academic citations

By default, if no other clear syntactic relation applies when an academic reference is supplied, it's root (usually a first author name) is attached to the root of the clause containing it as dep and the year is attached to the first author as nmod:unmarked:

However if the citation has a distinct syntactic function, the first author is taken as the head and the function is assigned as usual, for example here as the obj of the verb 'see':

References consisting only of a number, e.g. "[4]", function in the same way: the number is the head of the reference, and it is attached as dep to the local root unless it has another normal function (obj, nmod, etc.)

Multiple adjacent references are considered to be coordinated, whether or not an explicit 'and' appears:

- "... shown in many studies [1] , [2] and [3]" ( [1] dominates [2] and [3] as conj and [3] dominates "and" as cc)

- "... shown in many studies [1] , [2] , [3]" ( [1] also dominates [2] and [3] as conj)

Ranges of references with a hyphen are treated as a prepositional "TO" phrase:

- "... shown in many studies [1-3]" ([1] dominates [3] as nmod which dominates the hyphen as case)

¶ Saying verbs

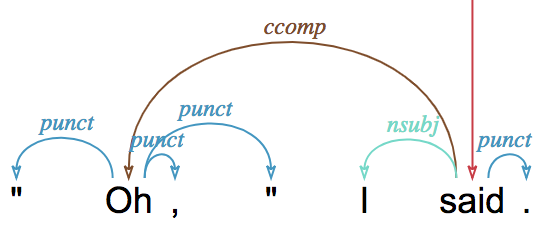

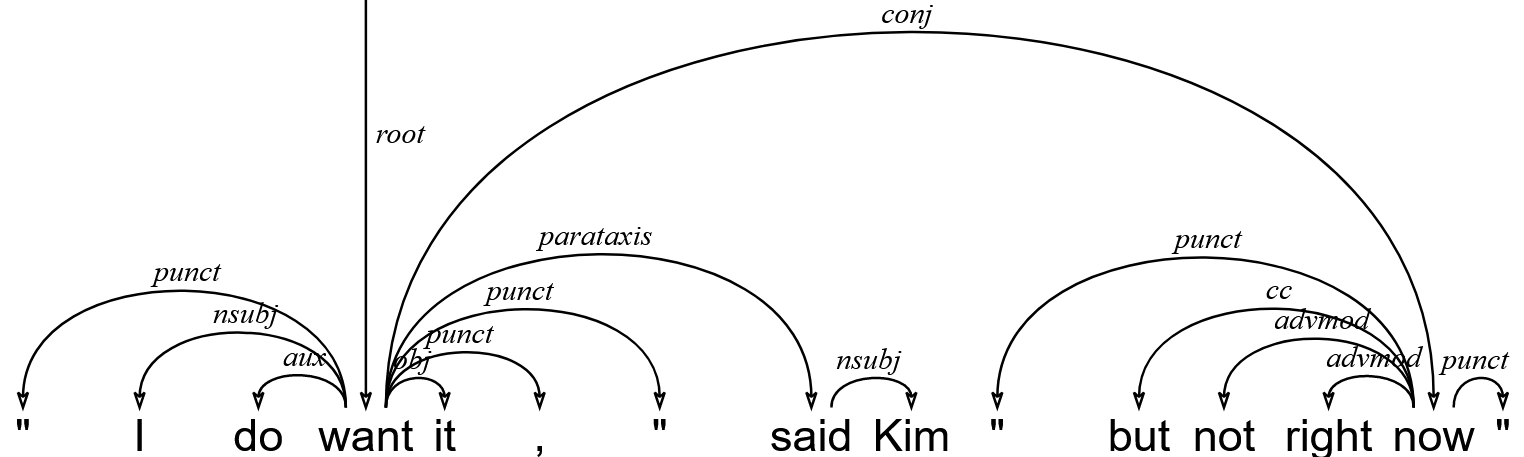

When the direct object of a saying verb is a quote, it is labeled as ccomp whether or not the quote is a full clause.

The exception is when the "X said" appears medially, in which case it is considered a parenthetical, with the verb of saying dependent on the speech's root as parataxis.

¶ Indirect objects of saying verbs

Verbs of saying can have two objects, direct (obj) and indirect (iobj). Both are present in

- John told Maryiobj the storyobj

In this case, Mary is the indirect object. It's important that, even if what is said is missing, the person being told is still iobj. For example, the following has iobj only:

- He told the policeiobj.

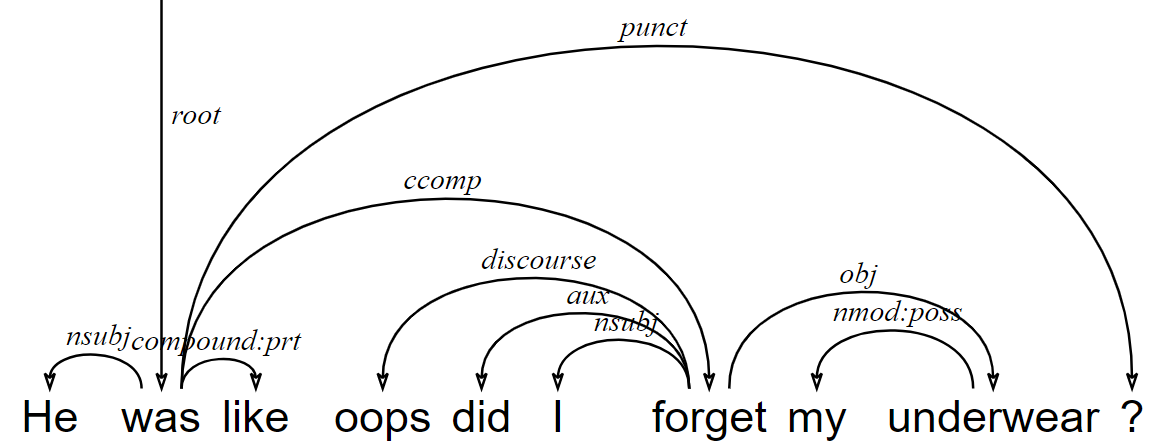

¶ be like

When used as an introducer of speech, based on EWT precedent, "be like" is treated as a phrasal verb with "be" as the head:

¶ Compounds

For compound nouns generally written as one word, or as two words separated by a hyphen, that you feel have been incorrectly split apart, treat the relation as an compound.

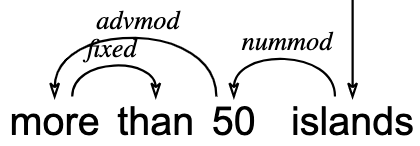

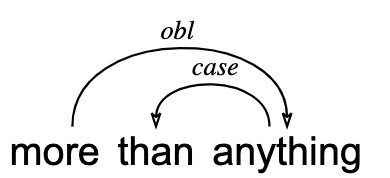

¶ more than

If more than is modifying a quantity, then the lexical word is the head. more than is a advmod which is internally a fixed.

If more than is used to compare things (a is more than b), then it is not a fixed, reverting to obl + case.

¶ Using fixed and goeswith

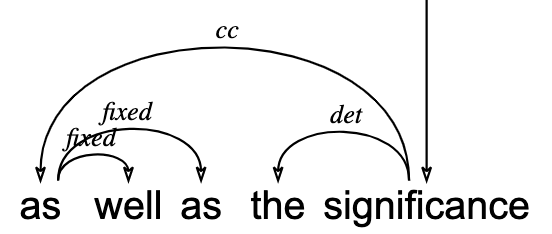

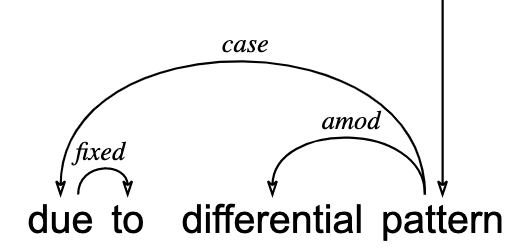

The fixed relation is used for certain multi-word idioms that behave as one function word. fixeds are always annotated head-initially.

¶ List of fixed expressions

The current list of fixeds includes the following expressions:

- according to

- all but

- all of (with quantities, as in: "all of five feet tall")

- as if

- as in (in the sense: "as in: I like it", not literally "as cold as in Oslo")

- as of

- as opposed to

- as such

- as to

- as well

- as well as (but not we didn't play as well as we thought)

- because of (and alternate forms, i.e. b/c of)

- depending on/upon

- due to

- each other

- had better (and 'd better)

- how come

- instead of

- in between

- in case

- in case of

- in order

- kind of (but not a kind of)

- less than (with quantities)

- let alone

- more than (with quantities)

- not to mention

- of course

- off of

- one another

- out of

- per se

- prior to

- rathercc than

- so as to

- so that

- sort of (but not a sort of)

- such as

- such that

- that is

- then again

- up to (with quantities)

- whether or not

¶ fixed vs goeswith

fixed dependencies should be limited to these specific expressions. If you have a word that seems to have been incorrectly split apart, such as with out, use goeswith instead. The head is what you feel is the "main" part of the word. goeswith should only be used as a last resort, when you feel like you have exhausted all other possible dependencies.