¶ Early Modern English letters

¶ Preamble

This is a guide to annotating Early Modern English letters.

¶ Annotation Guidelines

The guidelines will deal with several levels of analysis:

- Tokenization

- Utterance segmentation

- Part of speech tagging

- Constituent Parsing

- Dependency Parsing

¶ Tokenization

Tokenization in Early Modern English letters is quite standard. The process suggested for this particular variety adheres closely to the existing Part-of-Speech Tagging guidelines for the Penn Treebank Project as put forth by Santorini (1990). Challenging cases warranting discussion encountered in the corpus data studied are limited to the following:

¶ Title parsing errors

Retokenize parser output as needed so that all titles, e.g. "Mr.", are one token.

¶ Possession marking token

Complications arise sue to spelling and punctuation differences from Modern English, on which the existing guidelines are based. Instances specifically concerning possessive marking were encountered. An 's' character that can be clearly determined not to be plural based on the available context (in the utterance), and instead quite clearly appears (semantically) to be a possessive marker, should be treated as such. This requires retokenizing so that the 's' character and the noun it was previously attached to (the evident possessor nominal) are two individual tokens (rather than one). In this case, although the typical apostrophe does not precede the 's' character as it would normally according to standard English writing conventions, the possessive marking should still be treated as a separate token.

These decisions enable POS tagging (and subsequent syntactic annotation) to precede in these specific cases maximally accurately and, important to the goals of these guidelines, as it would have otherwise 'normally' preceded in standard English data.

¶ Utterance segmentation

Utterance segmentation in Early Modern English letters at first glance seems quite similar to that of standard, written English.

Ideally the segmentation process for this nonstandard variety would have preceded in a way that maintained a 1:1 ratio between sentences (as defined by sentence-ending punctuation) and utterances. However, the result of strictly segmenting according to sentence-ending punctuation would be extremely long utterances (often well over 125 tokens each). As this would make already challenging further annotation tasks even more difficult (and thus increase the likelihood for error on those tasks), a method was devised to reduce utterance length while maintaining maximally sentence-like units. The final decision involves treating semi-colons, in addition to sentence-ending punctuation, as utterance-ending punctuation. This is a simple, predictable way to achieve smaller utterances. Additionally, this is a logical choice, since semi-colons generally link complete sentences in standard English writing.

After application, initial worry that breaking up sentences into smaller utterances might result in obfuscation of original structure of potential interest was found to be generally unnecessary as utterances remained 'whole' standard sentence-like units.

¶ Part of Speech tagging

Part of Speech tagging in Early Modern English letters is overwhelmingly standard. No new tags are required. The process suggested for this particular variety adheres closely to the existing Part-of-Speech Tagging guidelines for the Penn Treebank Project as put forth by Santorini (1990). Challenging cases warranting discussion encountered in the corpus data studied are limited to the following:

¶ Spelling

Unfamiliar spelling can at times complicate POS identification. Most of the time, the differences in spelling do not hinder identification of the target token, especially when context is utilized (e.g., that Fryday is quite clearly 'Friday' does not require a great deal in terms of annotator-imposed 'analysis').

¶ Capitalization

Capitalization conventions for Early Modern English appear to be different from standard English conventions. The easiest, most predictable solution would be to conserve the "if capitalized, then assign NP"-style guideline of PTB, where non-sentence-beginning capitalization is consistently taken to indicate proper noun status. Despite the way it may seem at first, it does in fact make sense to maintain this rule for Early Modern English as well.

In this nonstandard variety, nouns that are quite evidently 'common' in nature can be capitalized. Exemplary capitalized nominals that could prove challenging for annotators are as follows:

- Remaine

- Secretarie

- Action

- State

- King

- Majesty

- (the) Court

- Erles

- Noblemen

- Chamber of presence

- Duke

- Counsellours

- Queene

- Ambassador

- Cittie

- Lord

Nominals that are easily identified as proper nouns (in standard English, too), such as country names, city names, and days of the week, of course remain analyzable as proper nouns and are thus assigned the POS tag 'NP'. Examples from the nonstandard data include:

- Fryday

- Saterday

- Finland

- Poland

- Waymouth

While it is tempting to try to divide these capitalized tokens into 'common' and 'proper' based on intuition and context, it is most reasonable to avoid further complication and simply continue to treat all tokens with non-sentence-beginning capitalization as 'proper' nouns, i.e. NPs. Arguably the greatest gain with this decision, aside from the practicality itself, is that the author's original intent and distinction is maintained (note that not all nouns were capitalized, so there is evidence for such author choices).

¶ Length and complex structure of utterances

The sheer length of utterances as well as the choices made regarding utterance segmentation can make it difficult occasionally to identify the subject of a given verb, resulting in difficulties choosing between a bare verb form (e.g., VV) or inflected verb form (e.g., VVP), which often have the same surface form. Efforts should be made to determine if an available subject is present in the utterance, keeping in mind that word order is apparently more flexible and that the intended subject could follow the verb form rather than precede it. If a plausible subject is present, the POS tag should indicate an inflected verb form. If however, there is no viable subject within that utterance, the verb form should be marked as bare. While some null subjects were discovered in the data, this seems to be fairly limited, and the decision-making process here is the one that should support results with the greatest amount of accuracy.

¶ Constituent Parsing

Constituent parsing in Early Modern English letters is quite standard. No new categories are required, and only one new function label has been added. The process suggested for this particular variety adheres closely to the existing Bracketing Guidelines for Treebank II Style Penn Treebank Project as put forth by Bies et al. (1995). Noticing that the existing PTB guidelines could basically handle the majority of this nonstandard variety's data, the decision was made to be particularly selective in terms of making changes or additions. Most of the time, the main hurdle is figuring out how to interpret and parse such long, complex utterances. With this in mind, remaining challenging cases encountered in the corpus data studied that warrant additional discussion are limited to the following (note that the new label is covered in the final section):

¶ Empty Elements

As a rule, the PTB preference for preserving S as being composed of an NP and a VP is preserved. For this nonstandard variety, this mostly translates to inserting null elements (and utilizing "traces") as appropriate. Other than accounting for non-overt subjects or complementizers, the data studied almost entirely follows this Sentence-category rule anyway. For both this reason and in order to create the most straightforward, predictable, and maximally accurate constituent trees, the decision to carry over this preference from PTB was made.

The guideline then basically boils down to: "add null elements (e.g., *, *T*, 0) where elements can be determined to be non-overtly realized but theoretically present." This should be followed consistently; the result is maximally useful trees for the study of Early Modern English syntactic patterns and tendencies.

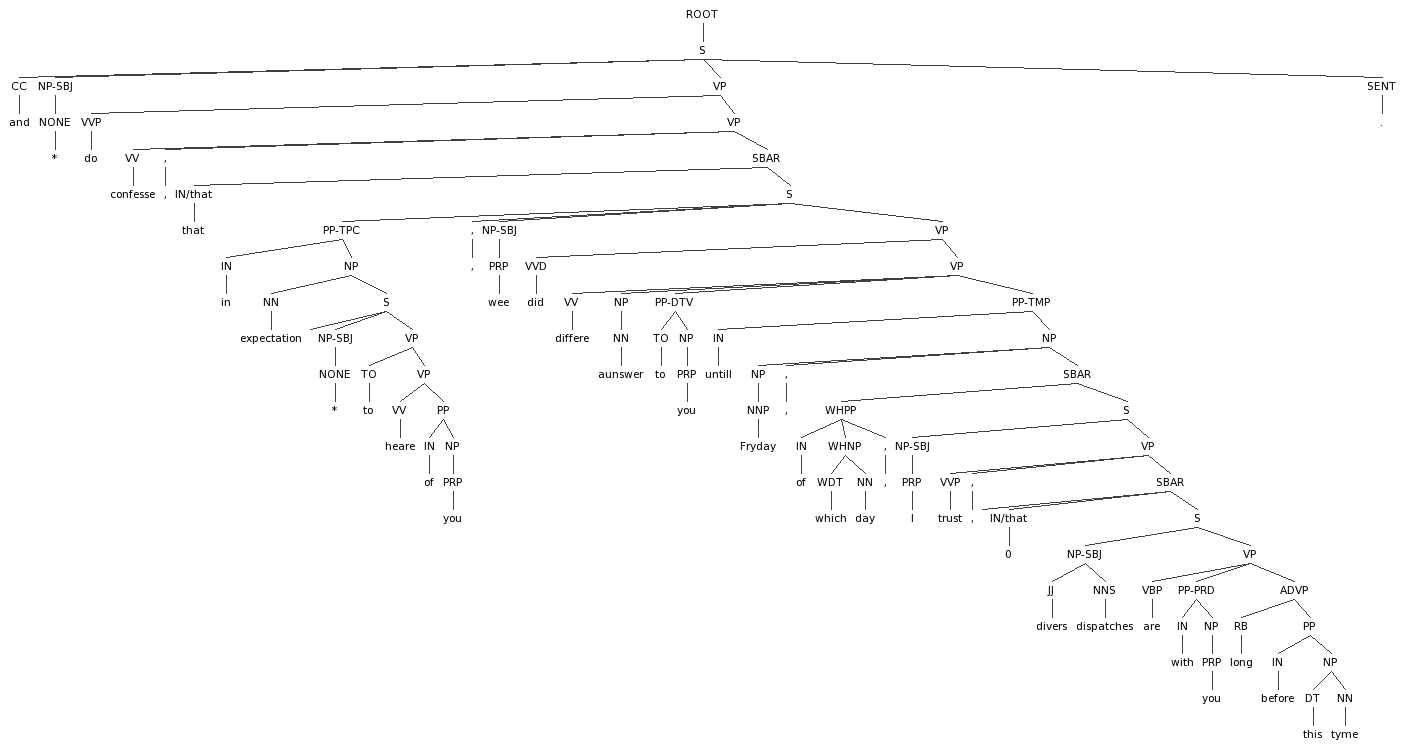

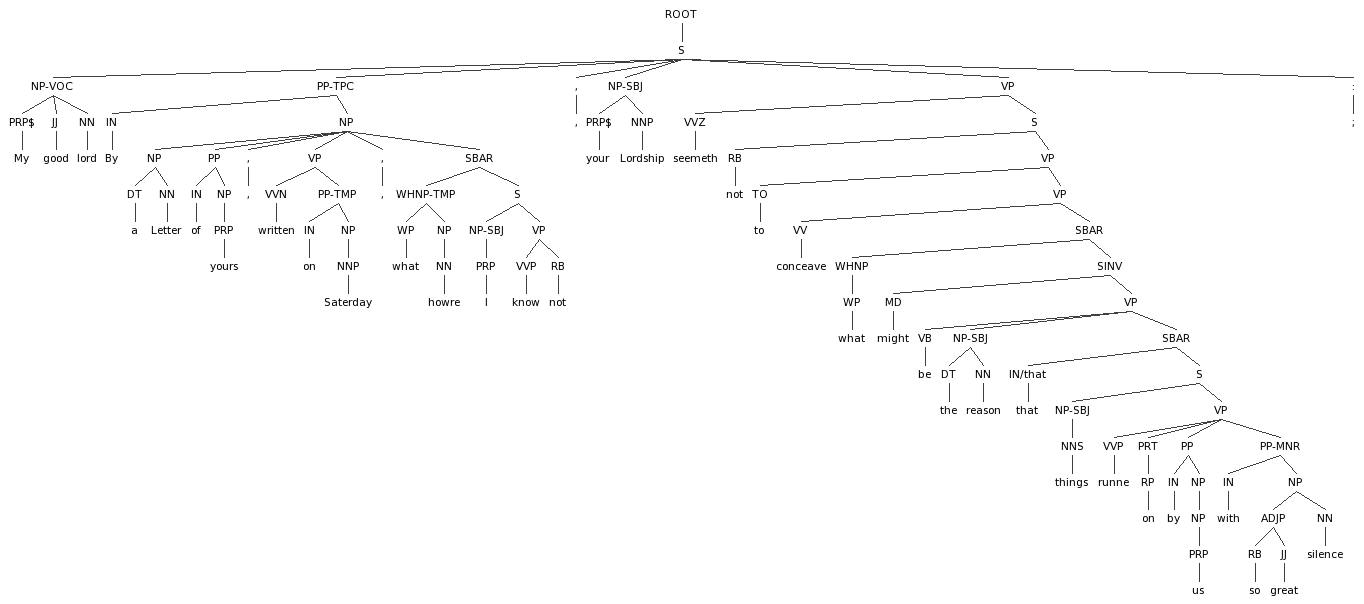

Example of appropriate null element incorporation:

¶ Null subjects due to utterance segmentation

Though I ultimately did not see this in the data I studied (the only apparent instance, upon more careful study, turned out to much more likely be an instance of a present post-topicalized-modificational-complement-clause matrix subject), this might be a potential concern given the decision regarding utterance segmentation. That said, it should generally not occur, because semi-colons do usually separate complete sentences. But, in the event that it is found to occur, a regular null subject (NP-SUBJ (-NONE- *)) should be inserted into the corresponding S. This is not entirely unrelated to the idea of omitted subjects in other language varieties, and does not represent a very large departure from the guidelines as currently formulated.

The temptation to somehow co-index these particular null elements might arise, if the 'intended' subject is clearly discernible from the context (e.g., present in the previous utterance and fitting with the semantics of the current utterance, also perhaps accompanied/supported by an inflected verb form manifesting subject-verb agreement). This should however be avoided completely. This would only overcomplicate the analysis, with little value in return. These null elements would not be some interesting case of licit null subjects, if in fact they are determined to be a direct result of utterance segmentation decisions, because they do (did) have a subject originally. For this reason, I don’t think they warrant special marking, as there is not any clear research-motivated reason to be able to track them down later. The question of the cost-to-value ratio of cross-utterance marking/relationships is then also skirted. Note that this would be quite a enormous departure from the previous guidelines, one happily avoided here (as one that would, for lack of a better expression "open a (gigantic) can of worms").

¶ Attachment ambiguities

Although this is not a "new" problem or one specific to the particular nonstandard variety of interest here, it is worth pointing out here that modifiers are often ambiguously analyzable. Early Modern English can complicate the situation when multiple modifiers of varying phrasal category are all topicalized or realized pre-verbally in a given utterance.

Per PTB premodifiers are placed inside the phrase they are associated with, unless VP-premodifiers, which are sometimes attached outside the VP at the S-level (depending on the semantics elated to the modifier in question). Postmodifiers are easier, in that they are generally always attached inside the phrasal category with which they are associated. As stated above, Early Modern English often places modifiers in series and locations more surprising or unexpected in comparison to standard English, which can very often complicate modificational phrase attachment. PTB has a guideline for handling ambiguity (Bies et al. 1995, p.15):

"When it is not clear whether a modifier within the VP should be attached at VP-level or to an object NP, the DEFAULT is to attach at VP-level (see section 5 [Pseudo-Attach])."

Respecting the goal (of the current guidelines) of minimal modification to PTB, this guideline is upheld and only minimally adapted/extended for Early Modern English. This rule should be applied, and then extended to include cases where (series of) modifiers occur before the matrix NP and VP. In these cases, where complete ambiguity remains because multiple readings are easily available even given the context, attachment should DEFAULT to inside the VP, rather than the NP. Keep in mind that movement from inside the VP to another position is quite likely, and should not inhibit following the guideline extension suggested here (e.g., placement of the trace inside the VP).

In the data studied, attachment was generally discernible from context (often not semantically compatible with the noun/NP anyway). However, the level of complexity of utterances encountered made it clear that this would be a potential issue for future annotation, and a guideline for such future challenges seemed warranted.

¶ Verb-Negation Order

Instances were encountered where negation does not appear on the side of verb as would be expected for standard English. This may very well be an artifact of the particular state of negation in a process of change over time at the point in time that the letters collected in the CEEC corpus were written.

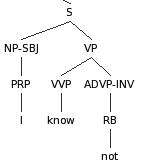

Example of utterance containing "inverted" negation "in the wild", unexpected negation placement relative to verb:

Because these instances could very possibly be of interest to later research on the syntax of Early Modern English, it was decided that a method for isolating them should be created, namely a new function label, -INV. This innovation is seen as sufficiently necessary, given the potential for research interest and the fact that PTB does not offer anything for marking these. A function label is the appropriate vehicle, but there is not any existing label that could simply be extended/adapted. A label is appropriate, in that it easily marks the elements of interest and even leaves room for other comparable cases of inverted word order (counter to expectations based on standard English) involving elements other than negation and verb placement specifically. The -INV label should be placed on the element in the "inverted" position.

Referring back to the example just above, the change given application of the suggested guideline would be as follows:

(S

(NP-SBJ (PRP I) )

(VP

(VVP know)

(ADVP-**INV** (RB not) )

)

)

)

Example of "inverted" negation, with new guideline applied:

Note that this particular example construction, negation inversion, can also be easily recognized by the lack of 'do-support' in these utterances.

¶ Dependency Parsing

Dependency parsing in Early Modern English letters is quite standard and straightforward. The process suggested for this particular nonstandard variety adheres entirely to the existing "Stanford Typed Dependencies" and the accompanying Stanford tag set. Noticing that the existing dependency guidelines and tags could quite easily handle this nonstandard variety's data, the decision was made to be extremely selective in terms of making changes or additions. The end result of these decisions is that no new dependency relations/labels are required. As with the constituency parsing, the main hurdle is figuring out how to interpret and parse such long, complex utterances. With this in mind, discussion of the few potentially challenging cases are limited to the following section, but it should be stated outright that dependency parsing as per the existing Stanford guidelines generally proceeds as expected for standard written English without additional difficulty.

¶ Empty elements

This is included here because it constituted an area of potential challenge and necessary analysis for constituency parsing. It should be noted that with dependency parsing, the process and outcome is quite different. The "issue" of null elements is basically skirted entirely. When the utterances are annotated for dependencies, there is no need to add null elements. The general focus of analysis is shifted from relationships between phrasal units to to relationships between words, so elements that are not present are not of any concern. The aim with dependencies is to understand what each element present relies on for realization. In sum, dependencies (versus constituents) simply (well, essentially nullify) the empty element issue.

¶ Obscure meaning

There are many levels to difficulties involving the determination of the meaning of a given utterance in Early Modern English. Of course, this is the nature of working with historical data, or any data non-native to the annotator. For instance, spelling can be challenging, because it can be quite different and also variable. Obviously there are some individual lexical items that are challenging because they are unfamiliar or unknown, and there is some challenge in interpreting morphological marking that is unfamiliar. Building on all of this, it seems the syntax too often obscures the meaning.

Simply put, the syntactic relationships can be challenging to figure out. For instance, the robust topicalization, often of several sizable phrasal elements at a time, makes even the seemingly simple task of identifying the matrix clauses in a given sentence quite a challenge. I’ve found that in comparison to constituency annotation, dependency annotation makes it significantly easier to parse things even when the meaning remains somewhat obscure.

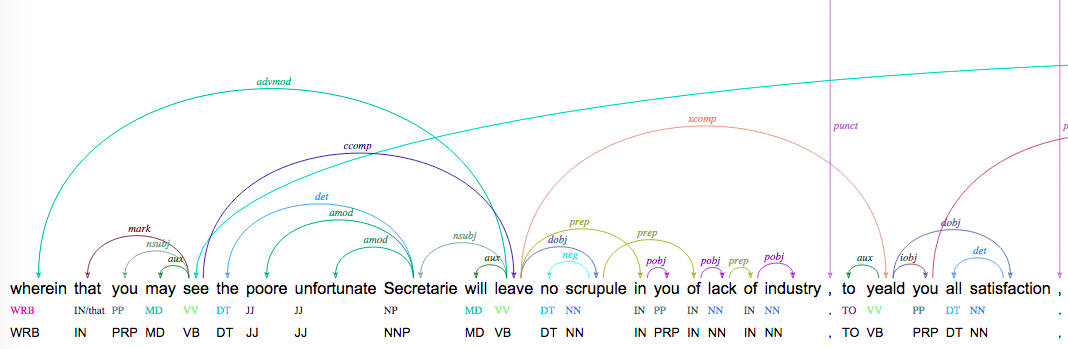

Example of less accessible meaning :

wherein that you may see the poore unfortunate Secretarie will leave no scruple in you of lack of industry, to yeald you all satisfaction

This demonstrates the many levels that complicate determining the meaning of the utterances. There are of course unfamiliar spellings of familiar words, potentially unfamiliar lexical items (wherein that, scruple, industry as used here), and argument structure and word order curiosities (yeald you, leave no scruple in you of lack of industry, and a complex ordering of the many modificational clauses). Yet, despite these clear obstacles, determining the dependencies between the individual words proceeds quite straightforwardly.

The point to be taken here is that the Stanford guidelines work surprisingly well as they are for handling this particular nonstandard variety.

¶ Concluding remarks

When in doubt, follow the existing guidelines referenced in the guidelines above. Surprisingly, these were almost entirely sufficient for predictably and accurately annotating Early Modern English data.